SIU President Delyte Morris appeals to students’ better angels in an attempt

to keep the university from closing in May 1970

“No progress is possible in a society where lawlessness prevails.”

— “The Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest”[1]

Day 3 to 5 – Friday through Sunday, May 8-10

The coverage plan conceived by Harry Hix and Lenny Granato didn’t anticipate an extended period of strife. “I would say our planning would pretty much figure that we would have an incident like the shooting at Kent State, and there would be maybe a riot or a demonstration or something or other that happened on a given day or night,” Hix said. “But not something that would go on tonight and tomorrow night and the next night and the next night.”[2]

Classes were not cancelled at SIU after Thursday night’s violence, but many classrooms were nearly empty the next day. Besides picket lines outside buildings urging students to boycott, a higher than usual number of SIU students already had left Carbondale in advance of the weekend. An official of the Illinois Central railroad reported that 500 students had boarded northbound trains on Wednesday and Thursday, a number that would have been large even for a Friday.[3] For the Daily Egyptian’s staff, classwork became secondary to covering the news.

“I don’t recall going to class,” reporter Bob Carr said. “If you were engaged, as I thought I was, with my first responsibility, which was reporting what was going on, there was too much happening. You had to be in too many places.”[4]

It wasn’t just students who felt that way. “After a night in the streets, the days were a blur,” Lenny Granato said. “I suppose I met my classes; they were still being held, but I cannot remember what affect the outside events had on classes.”[5]

For Marty (Francis) Milcarek, who had wanted to be a reporter ever since she was a 16-year-old columnist for her hometown newspaper, the chance to work on such a dramatic story meant everything. “This was our life,” she said. “To be on a campus and in a community where there was so much excitement going on, it was a dream come true.”[6]

From the moment a curfew was imposed in the early morning hours of May 8, Carbondale and SIU were communities under siege. National Guard troops manned barricades at entrances to campus. Military and police patrols aggressively enforced not only a dusk-to-dawn curfew, but also a ban on public gatherings of more than five people.[7] Chancellor Robert MacVicar extended the city’s emergency declaration to SIU, where gatherings of more than 25 persons were prohibited. Further, MacVicar decreed that any students arrested for violating curfew or any other emergency provision would be summarily suspended from the university.[8]

Restrictions on movement and free assembly were hard for students to accept after years of protesting university rules governing their private behavior. With large gatherings banned, conflict between young people and law enforcement did not end, but incidents were scattered, involved smaller numbers, were more spontaneous and less organized. Arrests continued, as did liberal application of tear gas. Only in a cluster of student apartment buildings east of the main campus was there a sufficient mass of students to mount a resistance.

“There were demonstrations and roads being blocked, bottles being thrown all over,” said Wayne Markham, the top student editor at the Daily Egyptian. “I also recall how difficult it was to get around for those of us who lived off campus. …There were security checkpoints, and I seem to recall that we tried to figure out where we could have people stay and be close to the newspaper.”[9]

Reporter Rich Davis described those days as “very eerie, very police state,” especially in the evenings when the curfew was in force.

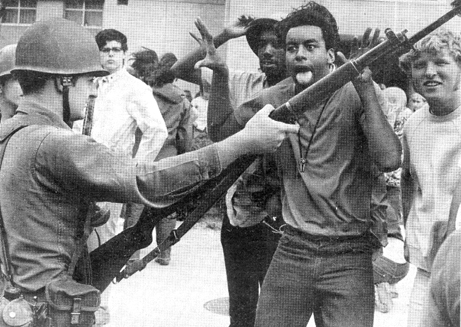

A SIU student taunts a National Guardsman

.in May 1970.

“People would stand out on the street, and the policemen and the National Guardsmen were in a caravan coming down the street with loudspeakers, telling people that they had to be in their homes or risk arrest,” he said. “There were students taunting police and the Guardsmen or whoever, and occasionally someone would throw something. I have these visions of students being chased into their dorms or down alleys. … Some students wanted to test the willingness of the police to come after them.”[10]

Just east of the Illinois Central railroad tracks, in an area SIU now calls the East Campus, were three, 17-story student apartment buildings, as well as three, four-story residence halls (since demolished). In 1970, these buildings were designated as University Park and Brush Towers. It was an area that got concentrated attention from law enforcement during the weekend.

The first test came early Friday night. A rally was scheduled to take place at University Park, beginning at 6 p.m., 90 minutes before curfew. Students were present, but due to what the Daily Egyptian described as a “lack of organization and the imposing presence of local and state police as well as National Guard troops,” no rally took place.[11]

Looking out from their dorm rooms, students saw National Guard troops standing shoulder-to-shoulder for the entire length of the block in front of Brush Towers, with city, SIU and state police arrayed behind them, and another line of troops behind the police. Small groups of students heckled the assembled force from their residences but did nothing else.

At 7:30 p.m., state police announced the start of the curfew. At 8 p.m., the National Guard withdrew from Brush Towers when it appeared that students would comply. Reporters were escorted around the city after curfew in National Guard and police vehicles. By 9 p.m. Friday night, reported the Daily Egyptian, “Carbondale was deserted and resembled a ghost town, with windows boarded up along downtown streets.”[12]

Daily reports of Carbondale authorities to the FBI office in Springfield assumed an almost cheery tone, compared to dispatches on the first two days of the crisis. “With the strict enforcement of the existing curfew, tensions on the campus have eased greatly and university officials feel that the crisis for the present is over,” an unnamed SIU Security official reported on May 9. Only minor clashes with law enforcement were reported to the FBI during the weekend, with no mention of significant violence, property damage or looting.[13]

Both the Daily Egyptian and the Southern Illinoisan noted the relative calm of the city under curfew, but their roundups of nightly mayhem and mischief made clear that calm did not mean quiet.

The Daily Egyptian reported on a fire in a two-story house overnight on Friday, which witnesses said was started by a tear canister fired into the structure by state police. Spectators threw rocks at firefighters as they tried to extinguish the blaze.[14] There were multiple reports of firebombs tossed here and there, and on Saturday, a bullet struck the front window of the Carbondale Police Department but did not pierce it.[15]

People congregating outside Holden Hospital and the Dairy Queen on Saturday were gassed by state police, who also fired tear gas canisters into a student apartment building on south Lincoln Street.[16] There were enough complaints of excessive police behavior for the Carbondale chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union to announce it was launching an investigation.[17]

One of those complaints involved a police raid Saturday on a home at 506 N. Bridge St. The house was a hangout for Carbondale’s SDS activists and staff of the underground newspaper Big Muddy Gazette. SIU Security Chief Thomas Leffler said his office initiated the raid after receiving complaints of unlawful assembly and curfew violations at the address. Leffler told the Southern Illinoisan that he believed the residence was the center “for everything that went on the past three days.”[18]

A resident of 506 N. Bridge examines debris left after a police raid at the home.

Police arrested 15 people. Occupants said they had no warning before tear gas was fired into the house. Forced to flee, they then were arrested outside for unlawful assembly. Daily Egyptian photographer Ralph Kylloe took photographs of the home’s debris-strewn interior, which residents said had been ransacked by police. Illinois State’s Attorney Richard Richman told the student newspaper that police did not obtain a search warrant for the property until the day after the raid.[19]

So many people were arrested Friday and Saturday nights in Carbondale that the Jackson County Jail in Murphysboro ran out of room. Some of the overflow went to the Williamson County Jail in Marion, where Carbondale scofflaws were accused of flooding a cellblock when they ripped out the plumbing fixtures. Other violators ended up in the Union County Jail in Anna and the Franklin County Jail in Benton.[20] According to reports received by the FBI from Carbondale that weekend, nearly 300 people were arrested Friday and Saturday nights.[21] One of them was Daily Egyptian reporter Bob Carr.

‘Get the reporter out here’

Carr and photographer Ralph Kylloe recall different details about the arrest, but both agree they were acting as journalists when they ran afoul of the law. At the time, the two were following the sound of breaking glass in the vicinity of University Park.

Carr said he identified himself to a state trooper as being with the Daily Egyptian and proceeded on his way. When he looked back, Carr said the trooper had Kylloe pinned against a wall. “I came over and said, ‘This is the photographer. We identified ourselves to you. We’re from the student newspaper.’ That’s about all I said, and he turned his attention from Ralph to me.”

Kylloe said he and Carr were handcuffed and taken to the Carbondale police station, where there were about 30 other young people who had been picked up by police. Kylloe said a SIU dean was there who knew he worked at the newspaper. Kylloe said he got the dean’s attention and pleaded his case. “He had the sergeant come over and un-handcuff me, and I took off.” By that time, Kylloe said, Carr already had been taken away, so Kylloe returned to the Daily Egyptian to report what had happened.[22]

Lenny Granato said he telephoned Journalism Department chairman Howard Long, who met him at the police station with bail money.[23]

“I was sitting in a jail cell – many, many others as well – and the shout went back, ‘Where’s the reporter? Get the reporter out here,’” Carr said. “So, I immediately thought, ‘That must be me.’ And I went out and they said, ‘You’re sprung. Get outta here.’”

Carr expected to be in trouble with the faculty, but instead, he said they were supportive and caring. “They were very much concerned with my wellbeing and with fair treatment. I think if anything, they were upset with the police for arresting me.”[24] Harry Hix said Long told him afterward to “not make anything more of it than it is. Let that go.”[25]

Carr’s name was dutifully reported in the May 13 edition of the Daily Egyptian in a lengthy list of names of people arrested during the weekend.[26] A preliminary charge was not specified, but the Southern Illinois reported it in its tally of arrests as disobeying a police officer.[27]

By Saturday, May 9, a curfew reduced disturbances to isolated incidents, some dealt with through use of tear gas.

The student newspaper was permitted by authorities to operate after curfew, but it was hardly business as usual for the staff of the Daily Egyptian. Besides later deadlines, students were supposed to wait for a police or National Guard escort to go off campus or to be taken to an on-campus dormitory. “Things would clear up enough by midnight that we could lock things up about that time and get the papers out somewhere around 1 or 2 (a.m.). Then we could get them home,” Hix said. “Lenny and I sat there and told war stories with them until we could finally get them out of there.”[28]

Daily Egyptian alumni said they didn’t always make it to their own home after those long nights. Wayne Markham remembered spending one night “kind of camping out” on a couch in one of the on-campus dormitories rather than returning to his off-campus residence.[29] Jim Hodl recalled being stuck at the Daily Egyptian office with other staff members when a police escort wasn’t available. “Everybody slept on the floor or a table,” he said.[30] Marty Milcarek said staff members often ended up at someone’s house after leaving the newspaper. “We all kind of just stayed with each other and supported each other and helped each other as we were trying to cover this,” she said.[31]

Hix said his undergraduate staff thrived that week. “Oh, they were ready to go,” he said. “This is exciting when you are 19 years old or 20. When something comes up, your blood kind of runs.”

Rich Davis agreed that covering the campus crisis was a rush for the young journalists in training. “It was big news. It was exciting,” he said. “You couldn’t believe this kind of stuff was happening. Taking over buildings. Fire bombings. There were hundreds and hundreds of police and the National Guard. And it was exciting to see this stuff happening, because what was happening in Carbondale were the kinds of things that were supposed to happen out in California or on the Big 10 campuses or out East. And it was happening in little old Carbondale.”

At the same time, Davis said, being on the streets with protesters and police could be daunting. “There was one night – I don’t remember which night – but we were in the heart of Carbondale, not far from the Varsity (Theater), and it seemed like there was a gas station nearby,” he said. “There were bricks and rocks being thrown, and I had this fear of being hurt. I also had this fear of something happening to the gas pumps. That night was very scary.”

Photographer John Lopinot said the experience helped set the course for his life. “It was all one big team,” he said. “We were all working together. I don’t ever recall any anger or shouting matches, anything but harmony. Everybody was getting along, trying to get that paper out. It was a great time. It was what really inspired me to go into journalism, I’d say.”[32]

A newspaper of record

The Daily Egyptian was unique among newspapers in Southern Illinois at the time of the Carbondale discord. The SIU newspaper was not only the largest morning newspaper in that part of Illinois nicknamed “Little Egypt,” it was one of only two morning newspapers in the southern third of the state.[33]

Exact circulation figures are unavailable, but information from Daily Egyptian files indicate a daily press run in 1970 of between 13,000 and 14,000 newspapers.[34] Only the Southern Illinoisan, one of many afternoon papers in the region, had a larger daily circulation at 26,974.[35] The only other morning newspaper served tiny Elkville in northeastern Jackson County. That meant when the citizens of the Carbondale area awoke each morning and wondered what the kids at SIU had been up to the night before, the most current source of information in print was the Daily Egyptian.

Harry Hix said his student reporters were aware that the Daily Egyptian was a newspaper of record during those days of unrest. It is one reason Hix said the newspaper extended its nightly deadline from 10 p.m. to midnight or later as circumstances dictated. “This was not a classroom exercise,” he said. “The students were thinking of themselves as professionals, and I liked to believe that Lenny and I played a role in that by treating them as professionals, referring to them that way and expecting them to write and behave that way. We didn’t talk to them as though they were students. It was a newspaper; it just happened to be put out on campus.”[36]

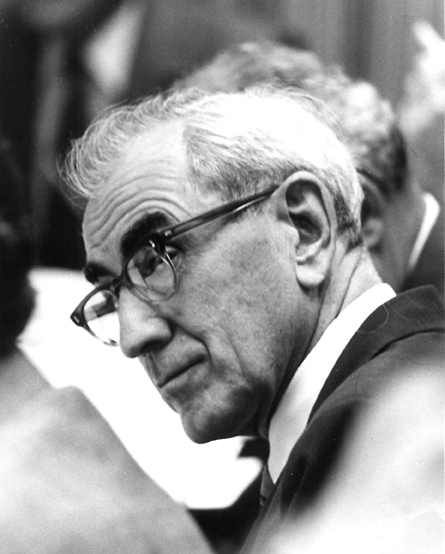

Howard Long

Ultimate responsibility at the Daily Egyptian rested with Howard Long, who came to SIU in 1953 as the Journalism Department’s first permanent chairman. He had a background in small town newspapers and had operated a weekly in Crane, Missouri, for several years. Long had done both his graduate and undergraduate studies at the University of Missouri, where he had been influenced by two pioneers of journalism education, Walter Williams and Frank Luther Mott.[37]

When the SIU administration approached Long in 1959 about taking over the biweekly Egyptian newspaper, then a student-run, extracurricular activity, the publication he proposed was based on the University of Missouri model. Key points were these: It would be edited by members of the journalism faculty, and it would provide professional training to students in a laboratory setting.[38] The first Egyptian under Journalism Department control appeared on September 19, 1961.[39] The newspaper did not begin daily publication until April 19, 1962. It was renamed the Daily Egyptian in 1963.[40]

“Big” is an adjective often used in describing Howard Long by those who worked with him at SIU. Big personality, big voice, big ambitions for the Journalism Department. He could be abrupt with people as well as forceful in his opinions. Long met daily with faculty assigned to the Daily Egyptian to review stories planned for the next edition, but he did not involve himself directly in newsroom operations.

“It was an atmosphere of freedom, an atmosphere conducive in terms of journalism of practicing the craft and pursuing the truth wherever it might lead you,” said Bill Harmon. “That was Howard Long’s only charge to me. I succeeded Harry (Hix), and it was the policy when Harry was managing editor. There was no story we couldn’t print if we had the facts for it.”[41]

Granato said Long would walk through the newspaper’s composing room during the days of crisis in May 1970 to look at pages before they went to press. “He never made a comment or a suggestion,” Granato said. “I asked him later why he had done that, and he replied that if anyone had complained about the coverage, he wanted to be in a position to say he’d read it before publication and it was just fine.”[42]

The Daily Egyptian published daily Tuesday through Saturday; nine editions were produced between May 5, the day after the Kent State shootings, to May 15, the day the SIU Board of Trustees voted to close campus for the remainder of the quarter. A content analysis of those papers done by the Journalism Department found that an increasing amount of news space was devoted to the turmoil as the days passed – from 24 percent of all available space on May 5 to 94.6 percent of all space on May 15. More than half of all non-advertising space was devoted to campus disorder for seven of those nine days.[43]

In addition to the content analysis, news sources and people mentioned in articles were contacted to see what they thought of the newspaper’s coverage. A total of 45 people were interviewed. The group included university officials, students, faculty, law enforcement, civic leaders and members of the Carbondale business community.

The interviews revealed that more of the newspaper’s stakeholders had a favorable opinion of the Daily Egyptian during its riot coverage than at other times. Of those surveyed, 69 percent were favorable of the Daily Egyptian’s coverage of the May disorders, while 20 percent had an unfavorable opinion. That compared to 60 percent who said they were favorably inclined toward the Daily Egyptian at other times, and 29 percent who said they generally held an unfavorable view of the newspaper.[44]

“I think there was an attempt at balance,” said Steve Brown, who was among those contributing notes each night to the staff reports. “I’ve never been a big believer in objectivity, just as a general principle, because I think once you learn something about a topic, that’ll show up in your writing. I think there was an attempt to be balanced and tell both sides of the story.”[45]

“The DE staff was a fairly tight-knit group, and I think we viewed the DE as “our” newspaper and that we were doing our jobs,” P.J. Heller said. “We were all students, so I think we all approached events from that perspective, but when it came to putting the information together into the DE, we did it from a professional perspective.”

Heller said it was a great help to have faculty and graduate assistants, all experienced journalists, working alongside students. “We were going through a period of unprecedented turmoil both on campus and in town and needed guidance to help us know both how to go about covering those events and making sure the coverage was fair and balanced,” he said. “It also helped us to know there were faculty members there who we could count on in the event of trouble when we were out reporting.”[46]

Day 6: Monday, May 11

By Sunday evening, Carbondale authorities felt the situation had improved enough to release all but 250 troops of the National Guard. Mayor David Keene cancelled the curfew for Monday night, but the ban on large gatherings remained in force. Any group of more than five people would be arrested if they did not disperse when told to do so by police.[47] “We are in a desperate situation,” Keene said in a statement. “This town has neither the resources nor the will to stand up under the continual attack of the young people. I am firmly convinced they had no concept of the psychological damage they have done.”[48]

Photo by John J. Lopinot | Daily Egyptian

A National Guardsman flashes a peace sign to a photographer in May 1970

as troops leave the campus of SIU in Cabondale.

The report from Carbondale to the Springfield FBI office on Monday advised “situation is under control and the city is calm.”[49] And it was until about 8 p.m. That was when groups began gathering in the downtown area in violation of the unlawful assembly crowd limits. Those who did not disperse when told to do so by police were arrested or gassed.[50]

“We usually will not throw tear gas bombs unless the crowd starts throwing rocks or if they just refuse to move when we ask them to break up,” one unidentified Carbondale policeman told the Southern Illinoisan, which reported on a rash of gassing incidents and minor fires overnight Monday, including the house on North Bridge Street that police had raided on Saturday. In that incident, Carbondale firemen said a firebomb had been thrown through a window and landed in a bathtub, doing little damage to the house.[51]

The University Park/Brush Towers area continued to be hot spot. Tensions flared up around 9 p.m. when police fired tear gas at Brush Towers as students taunted officers from their rooms and threw firecrackers and other debris at them. Around 10 p.m., students made a barricade of trash cans and started a fire in one of them. When Carbondale firemen arrived to put it out, students threw rocks at them until they left.[52]

An automobile was overturned on the street by demonstrators and set ablaze. At 10:30 p.m., SIU Dean of Students Wilbur Moulton ordered the doors of all University Park buildings locked to keep rock-throwers from using them as refuge. He announced through a bullhorn that any students gathered outside would be dispersed with tear gas. By 11 p.m., police were peppering the area with gas, and units of the National Guard were on the scene. The Daily Egyptian reported that an “apparent truce” was reached by midnight, allowing the troops and police to withdraw.[53]

The student newspaper’s account of the University Park/Brush Towers engagement was the first to raise the possibility of SIU closing due to the continued unrest. Carbondale Mayor David Keene was quoted as saying he thought there was a good chance the university would close. Police Chief Jack Hazel said he had been told closing was an option. However, Chancellor Robert MacVicar was not ready to discuss that with reporters. “School will continue as long as security can be maintained for those individuals involved,” he told the Daily Egyptian.[54]

And in this corner …

Rioting in Carbondale was largely the work of young, male, white SIU students. That was the recollection of Daily Egyptian staff who covered the unrest in May 1970, and it is supported by the historical record.

Both the SIU newspaper and the Southern Illinoisan printed extensive lists of names of persons arrested between May 6 and May 12. A review of those lists reveals that nearly 92 percent of all persons reported as detained by police had masculine first names. The youngest of those arrested was 16 years old; the oldest was 37. The majority fell between the ages of 19 and 23 years. Most of the addresses given were from Carbondale, nearby communities in Southern Illinois or the Chicago area, home to more than a quarter of the SIU student body that year.

The SIU Security Office reported in January 1971 that a total of 543 arrests had been made during the period of turmoil. Nearly 70 percent of arrests were for violation of city ordinances, such as being out after curfew or unlawful assembly. In 58 percent of cases, formal charges either were not filed, the charges were dismissed, or the person charged was found not guilty. Less than 30 percent of all cases resulted in a guilty finding.[55]

In April 1971, the SIU Alumni News published what it called a “wrap-up on campus disruptions.” The report stated that 323 SIU students were arrested the previous spring – nearly 60 percent of the total arrest figure cited in the Security Office memorandum. Of those students, 106 were convicted in state court and 166 were punished by SIU for violating the university’s disciplinary code. Code violations were dropped against 120 students after due process hearings. The report noted that only one African-American student received disciplinary action, which it stated indicates there was “little or no participation on the part of the university’s black students,” despite an African-American enrollment in Carbondale of about 2,500 students. About half of the students arrested and/or disciplined came from the Chicago area.[56]

Win Holden said he felt three groups of people were most responsible for the trouble in May 1970. “You had one group that was committed, anti-war, anti-establishment activists who saw this as a platform to make a visible statement,” he said. “Another group was what we now would call ‘experientials,’ people who wanted to be part of something, to see it. The third group was sort of the local young people for whom any activity at the university was a magnet. Clearly, the second group was the largest in terms of numbers. The first group was the most confrontational with authorities, closely followed by the third.”[57]

Absent from the arrest lists were names of well-known activists. Aside from four people arrested in the raid on the house at 506 N. Bridge St., only one name appeared of a person regularly mentioned in SIU security reports as an SDS leader or sympathizer. During the four days of curfew and restrictions on mass gatherings, people normally associated with large protests in Carbondale were not visible, based on accounts published in the Daily Egyptian and Southern Illinoisan.

“You would not see – as least I don’t recall seeing – a person who was in a leadership role breaking a window or doing something that was silliness violence,” Bob Carr said. “You would see that person in front of a parade or a march and shouting into a bullhorn. Yes, those people were in a leadership role, and they were acting appropriately, trying to lead people who didn’t necessarily care to be led but wanted some general direction on where they were going. When things started breaking apart, it’s every person for himself.”

Alexander Heard, chancellor of Vanderbilt University, served as a special adviser on campus sentiment to President Richard Nixon following the invasion of Cambodia. In a statement issued in July 1970, Heard said that Cambodia and the Kent State shootings intensified feelings among students who already were protesting the war or were discontent with society in general. “Before Cambodia, many of us on the campuses believed that deep disaffection afflicted only a small minority of students,” Heard wrote. “Now, we conclude that May triggered a vast pre-existing charge of pent-up frustration and dissatisfaction.”[58]

James Hodl said something like that happened in Carbondale once police started using tear gas to control students. “That was like throwing fuel on a fire,” he said. “It made students who wouldn’t have protested angry. Not everybody who went out on that march the last night was against the war in Vietnam. They were against the cops; they were against anybody in authority because of what they had gone through. Some of them felt they got a nose full of pepper gas, and they said, ‘What did I do to deserve this?’ ”[59]

Day 7, May 12: That’s all folks

One voice had been missing during the week of civil unrest in Carbondale. Neither seen nor heard was university President Delyte Morris, who for 22 years had been the unchallenged authority on everything about the university.

SIU President Delyte Morris

Morris wasn’t even in Carbondale for the worst days of violence on May 6 and May 7. SIU historian Betty Mitchell recounted in her book Delyte Morris of SIU that the university’s president had flown to Washington, D.C., at the end of April to meet with Illinois Sen. Charles H. Percy. From there, Morris went to Chicago for a meeting of the Illinois Board of Higher Education. Then it was on to Seattle, Portland, Corvallis (Oregon), San Francisco and Los Angeles. He arrived back in Carbondale on May 8 and spent part of each afternoon for the next three days at the National Guard Armory.[60]

Morris resurfaced in the public eye by way of a May 11 mention in the Southern Illinoisan, in which it was explained that Morris had been away on a “recruiting trip” when young people were vandalizing Carbondale’s business district.[61] The Daily Egyptian contacted Morris after midnight on May 11 to get his take on the night’s trouble at University Park. Morris told the newspaper that he didn’t know enough about the situation to comment.[62]

Later that morning (May 12), the University News Service released Morris’ first official pronouncement on the turmoil that had gripped the community for nearly a week. It was predictably resolute, typically uncompromising. “As a result of inquiries, I wish to state that neither campus of this university (Carbondale and Edwardsville) will close nor discontinue operation.” The statement went on to assert that every effort would be made to protect the university’s people and property, as well as the freedoms associated with an institution of higher learning.

“Those who choose to interfere with these freedoms may expect to be severed from the university if presently a part of it, and if not a member of the university family may expect the full force of the law and denial of access to university property,” Morris warned, echoing the tough rhetoric he had used for other disruptions of the academic routine. “May those students, faculty and others who understand the nature of a university join in an effort to preserve this university’s freedom, for those who would abuse freedom would kill it.”[63]

The university already had mailed letters to 150 students informing them of their suspension for violating curfew or other transgressions. “There will probably be more letters after the latest police reports are in,” Wilbur Moulton, SIU dean of students, told the Southern Illinoisan.[64]

“This thing had to come to a test”

In Texas-hold ’em poker, it’s called going “all in.” That’s when a player pushes all his chips into the middle of the table and declares their willingness to risk everything on one hand of cards. Essentially, that’s what Carbondale officials and university administrators did on May 12.

The major players all were represented at a 10 a.m. meeting to assess the situation: the mayor, the chancellor, four law enforcement agencies and the Illinois National Guard. Carbondale Police Chief Jack Hazel subsequently informed the FBI that it had been agreed that National Guard troops would return to their armories and students would be allowed to demonstrate without interference from police, as long as there was no destruction of property.[65]

Carbondale Mayor David Keene later defended his decision to rescind the state of civil emergency, which had been in effect for four days. “This thing had to come to a test,” he said.[66]

It didn’t take long for students to call the mayor’s bet. They began to gather around 6 p.m. on the lawn in front of Morris Library where the first big, post-Kent State rally had taken place on May 6. The crowd grew larger as the evening progressed and speakers railed against Morris’s threats and the city’s ban on mass gatherings.[67]

“When they say we can’t assemble, we must,” said Bill Moffett, a longtime anti-war activist in Carbondale. “Where is academic freedom when groups of more than four are arrested, when a family of five is a mob? There’s not going to be four here … There’s going to be 4,000. There’s going to be 20,000. Your final exams are not going to be in the classrooms; they’re going to be right here.” Moffett encouraged the crowd, which by that time numbered more than 2,000 people, to march downtown. However, he cautioned students to avoid a physical confrontation with authorities. “We want an orderly, peaceful, militant, anti-war demonstration,” Moffett said.[68]

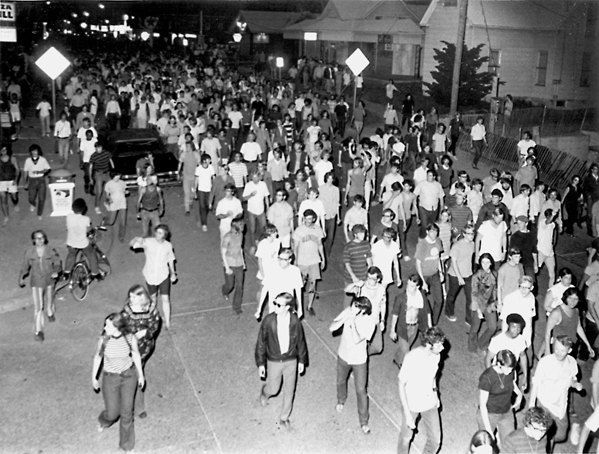

Students march through downtown Carbondale on May 12.

The crowd began moving around 7:30 p.m., first going to the University Park housing complex, then north to Main Street, adding people as they walked. SIU police watched the marchers pass the campus security office, but for a change, the officers were not wearing riot helmets or carrying clubs. Otherwise, law enforcement was not evident except at intersections, where vehicular traffic was routed around the procession.[69]

Daily Egyptian photographer Ken Garen shadowed the throng of students as it turned south on Illinois Avenue and headed toward campus. His photos of the crowd filling the street ran on the front page of the newspaper the next morning. “The weird thing about that evening was that the police just kind of pulled back and weren’t trying to control the students anymore. We weren’t quite sure where those orders came from.”[70]

The marchers passed the Carbondale City Hall around 8:30 p.m., where the doors had been locked to keep protesters out. Inside, the city council was voting on resolutions of appreciation for police agencies that had tried to maintain order during the civil emergency, as well as for the Illinois National Guard, Carbondale firefighters and the SIU administration. Roger Leisner, the SIU student representative on the council, read a statement deploring violence by students but also condemning actions of the Illinois State Police. Leisner was ruled out of order by Mayor David Keene, who said much of what Leisner was saying could not be substantiated.[71]

The crowd had grown to an estimated 5,000 people by the time it reached campus. Most of the marchers made their way to the lawn of the Morris’s residence and office, but they would not find the president and his wife, Dorothy, at home. SIU security had advised the couple to leave the premises before it was surrounded.[72]

Crowd surrounding president’s house on last night of protest.

“In the front, there was so much pushing that some people actually got pushed through the front window of Morris’s house. In the process of doing this, they knocked over some stereo equipment,” James Hodl said. “It’s open to debate whether they actually kicked in the windows on purpose and then trashed his stereo equipment. … It depended on where you were, how you saw it.”[73]

It is not a matter of debate that some windows, in fact, were broken or that some people did enter the home. Mrs. Morris later said there was evidence of small fires, perhaps started by fireworks, and all the food was taken from the refrigerator.[74] On a shelf of Delyte Morris’s clothes closet, she found a handwritten note, which had been left that night by intruders. It read: “We did the best we could to protect your house. If you believe in something strong enough, you’ll always stand up for it no matter where the mass goes. And we believe in peace that strongly. May God bless and protect you and your family.” The note was signed “Love and Peace, Lynda & Megan.”[75]

Destruction was not the goal of protesters squatting on the president’s lawn. The goal was to close the university. They told Chancellor Robert MacVicar as much when he arrived to speak with them. His assertion that he lacked the authority to do what they demanded was answered with cries of “close it now.” MacVicar then said he would advise Morris to consult with the SIU Board of Trustees by telephone yet that night. “I do not believe it is any longer possible for this university to operate on a normal schedule,” he said. It was 10:30 p.m.[76]

MacVicar reappeared a little less than an hour later. “We have done the only thing that is appropriate,” the chancellor said, addressing the students through a bullhorn. “The president has given me permission to announce that the university will be closed.” When students asked how long the school would be closed, MacVicar answered, “Indefinitely.”[77]

Chancellor Robert MacVicar, at left holding bullhorn, announces the closing of SIU shortly before midnight on May 12, 1970.

Ken Garen was watching through his camera’s viewfinder as MacVicar made the announcement. It was 11:20 p.m., with the newspaper’s deadline rapidly approaching. “I took a couple of shots during that and literally ran back to the Egyptian through the woods and broke the news to the staff.” However, Garen stayed long enough to see the mood of the crowd change “in a heartbeat from anger and confrontation to celebration at having won.”[78]

MacVicar told the students not to squander the moment on irresponsible behavior. “You have achieved your victory. Now don’t lose it with the activities of a few,” he said.[79]

City officials scrambled even as students began an all-night party in the streets of Carbondale. Mayor Keene ordered all taverns to close at 12:30 a.m. He tried to reach Gov. Richard Ogilvie by telephone at 2 a.m. to request the return of the National Guard. “They have taken the campus; we just can’t let them take the town,” he said.[80]

Jackson County Sheriff Raymond Dillinger had no luck convincing the superintendent of the Illinois State Police to send more troopers. “He just kept asking me who told the state police to go home,” Dillinger said to the Southern Illinoisan.[81]

The afternoon newspaper chronicled the celebration in its next edition, saying students greeted news of the closing with “cheers, revving engines, honking horns, shouting, arm waving, dancing up and down, and the clatter of empty beer cans hitting the pavement.”[82] The party continued until about 4 a.m. when a group of students began sweeping the street and picking up trash left by celebrants. Keene was not impressed by the cleanup effort. “They shouldn’t have been there in the first place,” he said.[83] However, the Carbondale mayor also told the Daily Egyptian that he supported the university’s decision. “He took the lesser of two evils,” Keene said of Chancellor MacVicar.[84]

Closing wasn’t something the Daily Egyptian staff had anticipated. “Í would say that even the people who were demonstrating, the majority of them didn’t expect to have classes canceled,” Ken Garen said. “They didn’t expect to be able to successfully close down the university. It came as a surprise to virtually everybody that it happened.”[85]

Harry Hix said the university had endured so much disruption during the school year that he didn’t believe the administration would capitulate. He thought the timing of the closure – only three weeks expected remained in the term – was a factor. “Had this happened in mid-April or the first of April, when shutting down the school would have had much greater impact, I am not convinced the same action would have been taken. …There wasn’t much time left before it would have been over anyway.”[86]

The SIU trustees still had to officially vote on the closure, and a meeting was set for May 15 at the university’s Edwardsville campus. That gave Delyte Morris a chance to make one final appeal directly to students, the majority of whom he believed loved the school as much as he did and wanted it to remain open.

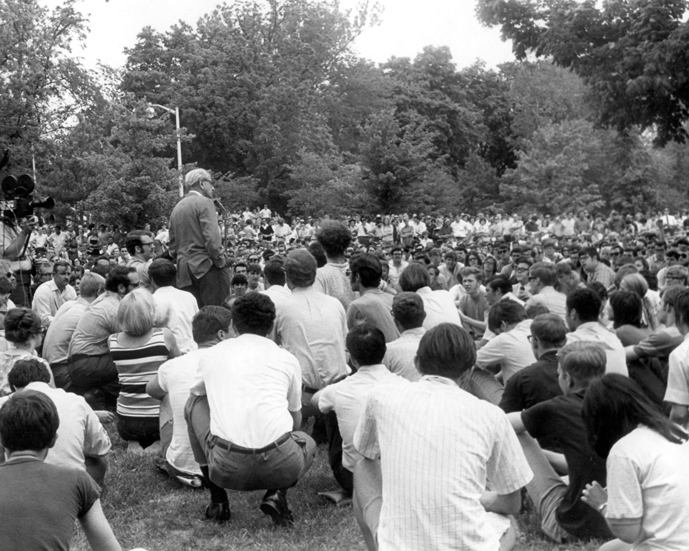

Delyte’s last stand

SIU President Delyte Morris meets with students who want

the university to remain open

.

“I must say, to me this is a welcome sight.”[87]

Delyte Morris was greeted by something he hadn’t heard in a while – cheers from thousands of students – when he appeared in front of the library that bore his name. It had been the scene of almost daily rallies since the death of anti-war protesters at Kent State University; however, this time, the green space was filled with students who wanted to go to class, not to protest or throw rocks at cops.

Twelve hours earlier, SIU had closed indefinitely after Morris’s on-campus residence had been surrounded by demonstrators. Now, here were as many or more students who disagreed with that outcome. The Daily Egyptian estimated the crowd at 3,000 people; the Southern Illinoisan doubled down and put the number at 6,000.[88] SIU Security reported the size of the crowd at 7,000 people to the FBI in Springfield.[89]

Morris told them SIU had been closed “under force of intimidation and threats of a riotous mob,” and he invited students to walk to his home and see the mess made by protesters the night before. Morris said the university would remain closed until it was clear that students wanted it reopened, and he seized on the idea of a campus poll to determine their wishes. “If the majority of students want the university to reopen again, it will reopen,” he said.[90]

After Morris left the rally to another ovation, the crowd was told that a vote of students and university staff would take place the next day at campus polling places used for student elections. The results would be submitted to the board of trustees on Friday.[91]

The rally had been organized by students wanting SIU to reopen, and most student speakers supported that position. Mike Ellis, an unsuccessful candidate for student body president that spring, called the events of the previous week “one of the saddest pages in this country’s history.” Ellis said the university was not the place for political issues.[92]

Friction was evident between students who wanted the university reopened and those sympathetic to the protests. The president of the Graduate Student Council was booed when he said the involvement of police and National Guard on campus was a mistake, and anti-war activist Bill Moffett was shouted down when he called Morris’s speech “demagogic.”[93]

A flyer appearing on campus warned of a “showdown” coming between student factions and an anonymous group of “older men” who had made threats against faculty and students.[94] Also being circulated was a petition to reopen SIU on behalf of students who objected to the actions “of the minority group that caused the crisis and forced the closing of the university.” The petition encouraged students to vote in favor of reopening the school. It stated, “The rest of us who intend to graduate … want to be heard.”[95]

Fear of new trouble prompted Mayor Keene to reimpose a dusk-to-dawn curfew and restrictions on mass gatherings. Three districts of the Illinois State Police sent troopers to bolster local law enforcement, and the governor agreed to send 1.200 National Guard troops to Carbondale to keep the peace.[96] In a message to the FBI in Springfield, the SIU Security Office reported National Guard troops were requested after receiving information that “some of the disruptive groups may clash with those desirous of attending the university.”[97]

Hearts and minds

Letters to the editor published in the Daily Egyptian between May 8 and May 13 reflected the anti-protest backlash. The following are excerpts from letter writers who identified themselves either as current SIU students or graduates:

“I’ve been one of the ‘Silent Majority’ for perhaps much too long. I’ve got something to say, and I think I have to say it – now, I’m sick of these so-called, self-styled ‘revolutionaries’ and their followers, not because of their beliefs or their programs; I’m sick of them because they talk about their ‘freedom,’ yet they don’t mind infringing upon the rights of others. …”[98]

“This has got to stop. I am sick of the same, few individuals trying to form coalition after coalition in an effort to destroy this campus. … I am sick of pigs (and I don’t mean the uniformed officers but the animals who run around destroying property) defecating, spitting, rock throwing, mercilessly beating the police and then having the unmitigated gall to yell police brutality when a man strikes back in the line or duty or in self-defense. …”[99]

“I wish to congratulate all the demonstrators for their superb results last week. The way I see it, you have expressed your inner feelings toward this campus and this country, and you have massed a maximum of 10-15 percent of the SIU student body to do this. This leaves 85-90 percent of the student body who either do not agree with you enough to demonstrate, think your actions last week were distasteful or they like this university and country the way it is …”[100]

“Well, it’s that time of year again. Some students, a minority, but still enough to merit recognition, have, like the rest of us, survived a long, cold, dull winter of university life. …They think very hard, and they decide destruction is the only way they can rid themselves of their pent-up emotions, and they know that the only institution in this country that will afford them this outlet is the university …And just one final suggestion to all of you so-called revolutionaries who think this country is so bad. Go throw a rock through a window in any other country and see where it gets you.”[101]

Daily Egyptian staff, some of whom were natives of Southern Illinois, said the local population had little sympathy for the demonstrators. “I know my mother thought it was horrible they closed the school,” said Rich Davis, who hailed from West Frankfort, Ill. “Here you’re working hard to get an education, and it’s all right to protest and not believe in the war, but violence and closing the school was just too much. She didn’t understand it.”[102]

The Carbondale business community, which already had borne brunt of property damage from the nights of rioting, faced more losses from the early closure of the university. “It’s going to ruin us when the university closes down,” the owner of Caru’s Suit Shop told the Daily Egyptian. “The bills don’t stop just because the university stops. Our business is 95 percent students.”[103]

State legislators contacted by the student newspaper also were displeased by events in Carbondale. State Rep. Gale Williams, R-Murphysboro, said SIU should do whatever was necessary to keep the taxpayer-supported school open for the full academic term. Rep. Clyde Choate, D-Anna, called upon the board of trustees to review the action of SIU administrators and to remove any found negligent or derelict in their duty. Trustees who did not wish to fulfill their responsibility could be replaced by the governor, Choate continued.[104]

The votes are in

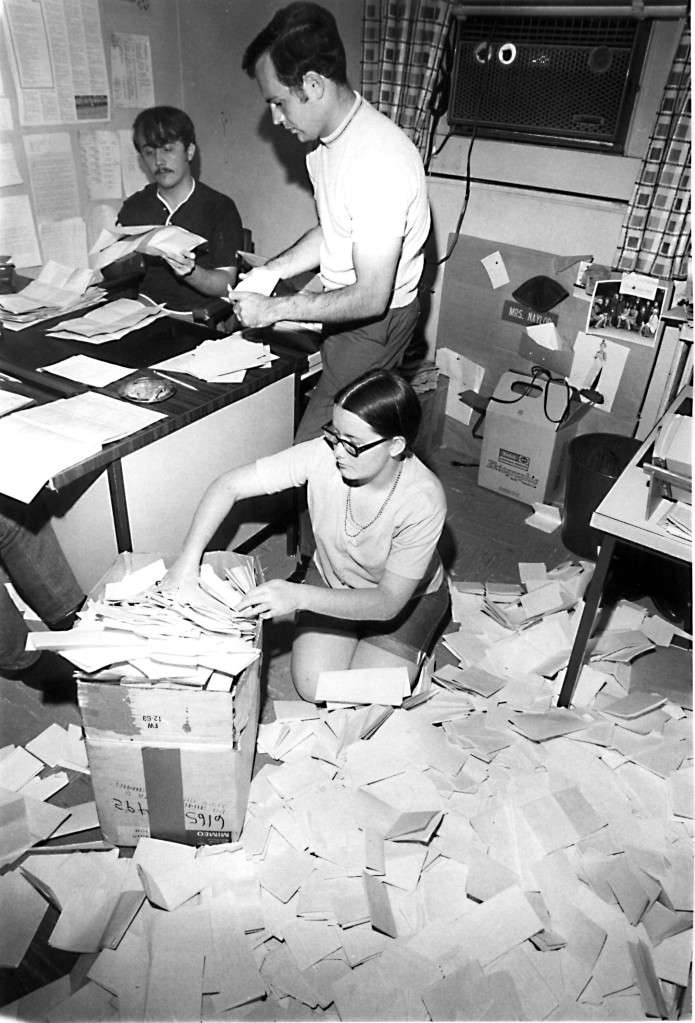

Voting for Delyte Morris’s opinion poll took place from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. May 14. The Daily Egyptian held the press until results were announced at 2 a.m. May 15. Despite the sentiment expressed at Wednesday’s library rally, students voted overwhelmingly to keep the campus shuttered. Two-thirds of more than 12,500 students who voted said SIU should remain closed. About the same percentage of faculty and staff wished to reopen, but they were outnumbered 6 to 1 by students.[105]

Volunteers count votes in closing referendum.

Nearly 11,000 students didn’t vote, based on a Carbondale enrollment of 23,002. Turnout might have been higher had not hundreds of students already had moved out of their rooms, according to a check of residence halls by the Daily Egyptian. Even before the trustees met in Edwardsville on Friday, the university had given students until Saturday morning to vacate the dormitories.[106]

Harry Hix said he thought Morris was “whistling in the wind” if he believed reopening the university was possible. “A lot of people started clearing out immediately as soon as they said there were no more classes; people were disappearing all over the place,” Hix said. “The disruption was maybe not total, but it was sufficient that once that decision (closing) was made and announced, I don’t see how you could retract it.”[107]

“It was sort of like a volcano erupting,” Rich Davis said. “All these events had culminated with the closing, and it had relieved this pressure. I think a lot of the students, selfishly, were glad it was over, and maybe they were looking for an excuse to take a break and get away from school for a while. So, I was never sure if a majority of students sincerely believed it was right to close the campus.”[108]

Final say on the end of the school year rested with the university trustees, who met on May 15 at SIU’s Edwardsville campus, across the Mississippi River from St. Louis. In existence only since 1965, its enrollment had grown to more than 12,000 students in just four years.[109]

Joining the deliberations was Illinois Gov. Richard Ogilvie, who met with the board in closed session from 10 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. In his biography Richard Ogilvie: In the interest of the state, author Taylor Pensoneau noted the ways SIU had gained attention during the Ogilvie administration: an arson fire that destroyed its oldest building, Old Main; the controversy about an expensive new residence for its president; and civil unrest after Kent State.

“In the years since World War II, SIU had grown from a modest teachers’ college to a university of prestigious scope,” Pensoneau wrote. “As this evolved, SIU at Carbondale was not known for restraint, whether in academic expansion, in play by students or, as shown during the Ogilvie era, in rioting.”[110]

Several students and faculty members attended the meeting in Edwardsville; some waited in a hallway outside the conference room where the proceedings were broadcast over a public address system. A dozen students were given three minutes each to speak to the board, which also heard from the chancellors of the two SIU campuses and faculty representatives. After a second closed session to review the testimony, the board voted 4-1, with three members not present, to approve a resolution keeping the Carbondale campus closed through June 13, the end of the spring quarter. Board member E.T. Simonds of Carbondale cast the lone dissenting vote.[111]

Ogilivie said he did not think the SIU trustees had any choice but to keep the campus closed, noting that it probably was asking too much to “keep universities open with bayonets.”[112]

Among SIU students at the meeting was Rich Davis, who was reporting for the Daily Egyptian. His coverage of the event turned out to be the most important story he ever wrote that never saw print.

“On the way back to campus – those were the days of the old manual typewriters – we were sitting in the Egyptian’s car, and there were two or three of us,” Davis said. “I had the typewriter in my lap. We were typing our story. …but we get back to the Egyptian and they tell us, ‘Don’t worry about it. Since the campus is going to stay closed, we’re not going to publish tomorrow.’ I was furious. I was really angry. How could we not come out tomorrow? What kind of newspaper are we?”[113]

By not publishing on May 16, there was another significant news event that was not in the Daily Egyptian – the killing of two African-American students by police gunfire at Jackson State College in Jackson, Miss. The shootings – 12 other students were injured in a hail of bullets around midnight on May 14 – kept unrest going at colleges that hadn’t closed.[114]

And in the end …

Many students wasted no time leaving campus after its closing was announced.

Just like that, it was over. The story was finished; another chapter of SIU history had slammed shut.

There were mixed feelings about how the year ended among the Daily Egyptian staff. Some were delighted that all grades for the quarter were going to be pass/fail. “For me, it was actually a good thing since I had spent so much time at the DE during the quarter that I had barely been to any classes,” P.J. Heller said. “Fortunately, most professors gave out pass grades if they had seen you in classes.”[115]

Others were not as pleased. Nathan Jones, a four-year staff member, still resents not getting to finish the journalism law class he was taking his final quarter of college. “As far as I was concerned, I still had three weeks to read my 400 pages of journalism law,” he said. “I’m always better when it’s fresh in my head, rather than reading it too early and having it disappear. To this day … I’m still waiting to read my 400 pages of journalism law. And I’ve already paid my tuition.”[116]

Marty Milcarek experienced both happiness and anxiety. She was happy to pass a difficult science class she needed to graduate that spring. She was anxious about the impact on her post-graduation job search. “By closing down, some of your contacts and some of the people who were interviewing – that wasn’t going to happen,” she said. “I didn’t have a job at the time school closed. I got the job later, maybe in the middle of June.”[117]

The job she took was with a regional bureau of United Press International in Pittsburgh. The next year, Milcarek said, she was assigned to call the parents of two students who had been killed at Kent State.[118]

The Daily Egyptian didn’t publish again until June 23. Much of the staff came back for the summer, but there was a sprinkling of newcomers among the veterans, the latter still telling war stories about what became known around the Daily Egyptian as “Seven Days in May.” There also was a new boss. Bill Harmon, who had assisted Harry Hix at the newspaper, now sat in the chair reserved for the faculty managing editor. It would be the last quarter the newspaper would be produced in the old barracks; by fall, the Daily Egyptian would move into a brand new building for the College of Mass Communications.

The first newspaper of the summer carried ripples from the current of disquiet in the streets of Carbondale. On Page 5 was the text of a statement given by Delyte Morris to the board of trustees on June 19, when the board had accepted Morris’s request to step down as president of the university after 22 years in charge. Morris would retain the title of president until September 1, when he technically would become president emeritus for another year. It marked the end of the career of a man who still is remembered as the “father of SIU.”[119]

Hix moved on from SIU to teach for two years at Southwest Texas University (now Texas State University); then, he returned to newspapering in Tennessee.[120]

Lenny Granato eventually wound up in Brisbane, Australia, where he taught journalism and was involved in community theater. He died in 2004. Wayne Markham had a three-decade career with the Miami Herald; the last 14 years, he served as publisher of the Herald’s Florida Keys publications, the Keynoter and the Reporter. He passed away March 6, 2020, after a short illness, according to his obituary in the Miami Herald.

Sigma Delta Chi, the Society of Professional Journalists, would give the Daily Egyptian a national newswriting award for its coverage of the May riots.[121] It was a nice honor for the collegiate publication, but Hix already had experienced a special moment of recognition with his staff. He said it came at the end of the first night of rioting in Carbondale.

“I do remember that night when it was all over, and we gathered in the newsroom to look at the paper, marveling over what was happening to us,” Hix said. “I think that’s when it dawned on me that, gee, these folks did what we asked them to do. What we had planned really did work. … If there was a particular moment, it would be when we were all looking at a copy of the paper, right off the press, and all the students were standing around. Everybody is still excited, and some of them are dirty and sweaty. There’s still an adrenalin flow.”

The former Daily Egyptian building, circa 2003. The building was demolished in June 2006.

-30-

Endnotes: Chapter 7

[1] “The Report of the Commission on Campus Unrest,” reprinted in The Chronicle of Higher Education, 5 October 1970.

[2] Hix, interview.

[3] “Sharp increase reported in ticket sales,” Daily Egyptian, 8 May 1970.

[4] Bob Carr, interview by author, telephone, 17 September 2002.

[5] Lenny Granato, interview by author, electronic mail, 24 August 2002 to 28 January 2003.

[6] Marty (Francis) Milcarek, interview by author, 28 February 2003.

[7] “$100,000 damages to city, SIU,” Daily Egyptian, 12 May 1970.

[8] Special bulletin, office of the Chancellor, Carbondale campus, 8 May 1970. “Civil emergency prompts curfew,” Daily Egyptian, 9 May 1970.

[9] Wayne Markham, interview by author, 29 March 2004.

[10] Rich Davis, interview by author, 21 July 2002.

[11] “Calm returns to Carbondale; curfew still on,” Daily Egyptian, 9 May 1970.

[12] Ibid.

[13] FBI Springfield to Director, author unknown, status updates on situation in Carbondale, 9 May 1970, 10 May 1970 and 11 May 1970, Freedom of Information Act request No. 0991941, U.S. Dept. of Justice.

[14] “Calm returns to Carbondale; curfew still on,” Daily Egyptian, 9 May 1970.

[15] “Most troops pull out; Keene rescinds curfew,” Southern Illinoisan, 11 May 1970.

[16] Max Turner, “Chronology of Events Related to the Closing of Southern Illinois University,” C. Thomas Busch Collection, Box 5, Folder 13, Special Collections, Morris Library.

[17] “Gassing prompts ACLU probe,” Daily Egyptian, 12 May 1970.

[18] “Police suspected raided house was ‘headquarters,” Southern Illinoisan, 12 May 1970.

[19] “Police close raid records,” Daily Egyptian, 13 May 1970.

[20] “Williamson Jail ‘a mess,’” Southern Illinoisan, I10 May 1970.

[21] FOIA documents.

[22] Ralph Kylloe interview by author, 30 September 2002.

[23] Granato, interview.

[24] Carr, interview.

[25] Harry Hix, interview by author, 20 September 2002.

[26] “Persons arrested Friday, Saturday and Sunday,” the Daily Egyptian, 13 May 1970.

[27] “Most troops pull out; Keene rescinds curfew,” Southern Illinoisan, 11 May 1970.

[28] Hix, interview.

[29] Markham, interview.

[30] Jim Hodl, interview by author, 9 February 2003.

[31] Milcarek, interview.

[32] John Lopinot, interview by author, 18 September 2002.

[33] Editor & Publisher Yearbook, 1970.

[34] A Daily Egyptian annual report for 1967 gives the circulation as 14,000 copies per day. An undated internal memorandum titled “Review notes of Daily Egyptian circulation” report the daily press run as 13,000 copies for 1971. The memorandum stated that there were no exact circulation files or records prior to 1983. Both records were found in the files of the Daily Egyptian’s general manager.

[35] Op cit.

[36] Hix, interview.

[37] Earl E. Parkhill, “The History of the Department of Journalism, Southern Illinois University,” (master’s thesis, Southern Illinois University, 1971).

[38] Charles D. Tenney to Delyte Morris, memorandum, 30 March 1959, Box 415, Journalism folder, President’s Office Collection, Special Collections, Morris Library.

[39] “University Aims for Daily Status,” The Egyptian, 19 September, 1961.

[40] “75 years of the Daily Egyptian,” Anniversary Edition, 11 March 1962.

[41] Bill Harmon, interview by author, 21 August 2002.

[42] Granato, interview.

[43] “A Quantitative Analysis of the Content of the Daily Egyptian during the May Disorders at SIU,” Kenneth Starck, Ph.D., Department of Journalism, Southern Illinois University, undated.

[44] “Selected source attitude toward the Daily Egyptian generally and its coverage of the May disorders at SIU,” Kenneth Starck, Ph.D., Department of Journalism, Southern Illinois University, undated.

[45] Steve Brown, interview by author, 27, February 2003.

[46] P.J. Heller, interview by author, by email, 10 September 2002 to 9 December 2002.

[47] “Most troops pull out; Keene rescinds curfew,” Southern Illinoisan, 11 May 1970.

[48] “Civil emergency ends; gatherings prohibited,” Daily Egyptian, 12 May 1970.

[49] Springfield FBI to Director, author unknown, teletype, 11 May 1970.

[50] “SIU officials plan meeting on state of campus,” Daily Egyptian, 12 May 1970.

[51] “Disturbances continue,” Southern Illinoisan, 12 May 1970.

[52] Turner, chronology.

[53] “SIU officials plan meeting,” Daily Egyptian.

[54] Ibid.

[55] SIU Security Office, n.a., report of arrests made during disturbances at SIU, 6-18 May 1970, Box 662, Student Dissent folder, President’s Office Collection, Special Collections, Morris Library.

[56] “Wrap-Up on Campus Disruptions,” author unknown, Alumni News, Vol. 32, No. 9, April 1971.

[57] Win Holden, interview by author, 2 May 2003.

[58] Alexander Heard, statement, 23 July 1970, Thomas Busch Collection, Special Collections, Morris Library.

[59] James Hodl, interview by author, 9 February 2003.

[60] Betty Mitchell, “Delyte Morris of SIU,” (Southern Illinois Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville, 1988).

[61] “Campus quiet, classes meet,” Southern Illinoisan, 11 May 1970.

[62] “SIU officials plan meeting,” Daily Egyptian.

[63] University News Service, statement of Delyte Morris, 12 May 1970, Box 569, General Correspondence folder, President’s Office Collection, Special Collections, Morris Library.

[64] “150 SIU students get letters of suspension,” Southern Illinoisan, 11 May 1970.

[65] Springfield FBI to Director, author unknown, teletype, 13 May 1970. FOIA.

[66] “Keene: ‘This thing had to come to a test.’” Southern Illinoisan, 13 May 1970.

[67] “SIU closed indefinitely,” Daily Egyptian, 13 May 1970.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Garen, interview.

[71] “City Council votes praise for police,” Daily Egyptian, 13 May 1970.

[72] “Minor damage inflicted on President’s home, office,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May 1970.

[73] Hodl interview.

[74] Op cit.

[75] Handwritten note, author unknown, Vertical File Manuscript No. 1667, President’s Office Collection, Special Collections, Morris Library.

[76]Turner, chronology.

[77] “SIU closed indefinitely,” Daily Egyptian, 13 May 1970.

[78] Garen, interview.

[79] Op cit.

[80] Turner, chronology.

[81] “Keene: This thing had to come to a test,” Southern Illinoisan, 13 May 1970.

[82] “ ‘Right on, man, right on!’ “Southern Illinoisan, 13 May 1970.

[83] Op cit.

[84] “Keene proclaims new emergency; curfew on again,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May 1970.

[85] Garen, interview.

[86] Hix, interview.

[87] “Morris supports campus poll at rally,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May 1970

[88] Ibid; Morris promises vote on reopening SIU,” Southern Illinoisan, 13 May 1970.

[89] Springfield FBI to Director, author unknown, teletype, 13 May 1970, FOIA.

[90] “Morris supports campus poll at rally,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May1970.

[91] “Closure continues; Board to decide future of campus,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May 1970.

[92] Op cit. Student election results from “Student’s Party takes top two,” Daily Egyptian, 30 April 1970.

[93] “Morris supports campus poll at rally,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May1970.

[94] “Flyer warns of radical factions,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May 1970.

[95] “Student petition shows support for referendum,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May 1970.

[96] Keene proclaims new emergency; curfew on again,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May 1970.

[97] Springfield FBI to Director, author unknown, teletype, marked urgent, 13 May 1970, FOIA.

[98] “Coed sick of revolutionaries,” Pat McLean letter to the editor, Daily Egyptian, 8 May 1970.

[99] “Destruction is work of pigs,” Jeffrey Disend, letter to the editor, Daily Egyptian, 13 may 1970.

[100] “Congratulations to demonstrators,” Bob Caraker letter to the editor, Daily Egyptian, 13 May 1970.

[101] “Spring brings out students,” Ron Darnell, letter to the editor, Daily Egyptian, 12 May 1970.

[102] Davis, interview.

[103] “Local merchants speak on closure,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May 1970.

[104] “Choate asks review,” Daily Egyptian, 14 May 1970.

[105] “Closure voted by students; reopen say faculty-staff,” Daily Egyptian, 15 May 1970.

[106] “Deadline for checkout extended 24 hours,” Daily Egyptian, 15 May 1970.

[107] Hix, interview.

[108] Davis, interview.

[109] “Edwardsville Enrollment Hits 10.000 Mark in 4 years,” Obelisk yearbook, Centennial Edition, 1969, p. 78.

[110] Taylor Pensoneau, “Richard Ogilvie: In the interest of the State,” Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville, 1997, p. 165. Richard Ogilvie was the 35th governor of Illinois. He served one term from 1969 to 1973.

[111] “SIU closed until June 13,” Southern Illinoisan, 17 May 1970.

[112] Op cit.

[113] Davis, interview.

[114] President’s Commission on Campus Unrest.

[115] Heller, interview.

[116] Nathan Jones, interview by author, by telephone, 27 September 2002.

[117] Milcarek, interview.

[118] Ibid.

[119] “Morris requests retirement in statement to SIU trustees,” Daily Egyptian, 23 July 1970.

[120] Hix, email to author, 24 April 2006.

[121] Obelisk, SIU yearbook, 1972.